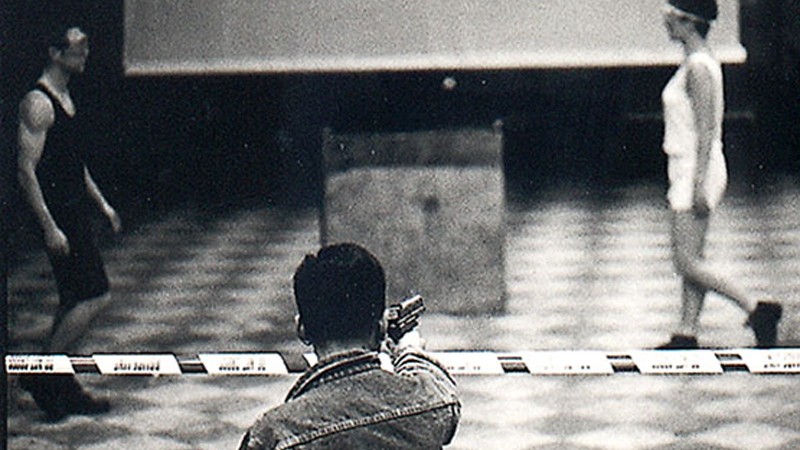

Along with Botfighters, Can You See Me Now? is one of the first location based games. Online players navigate a 3D map of a city-centre game area, whilst Blast Theory runners are on the streets for real. Runners chase after online players, using mobile devices to follow their location live, whilst runners' positions are tracked by satellite and updated in real time on the 3D game area. With up to 100 people playing online at a time, players use text chat to exchange tactics and send messages to the runners. An audio stream from the runners' walkie talkies allows players to eavesdrop on their pursuers: getting lost, cold and out of breath on the streets of the city.

This project was the second major collaboration with the Mixed Reality Lab at the University of Nottingham after Desert Rain. It was developed during a long period of research and development in London and Nottingham exploring Global Positioning Systems and wireless networking.

Can You See Me Now? takes the fabric of the city and makes our location within it central to the gameplay. The physical city is overlaid with a virtual city to explore ideas of absence and presence. By sharing the same ‘space’, the players online and runners on the street enter into a relationship that is adversarial, playful and, ultimately, filled with pathos.

As soon as a player registers they have to answer the question: ‘Is there someone you haven’t seen for a long time that you still think of?’. From that moment issues of presence and absence run through the game. This person – absent in place and time – seems irrelevant to the subsequent gameplay; only at the point that the player is caught or ‘seen’ by a runner do they hear the name mentioned again as part of the live audio feed from the streets. The last words they hear are the runner announcing their catch, referring to them by the name of the person they haven’t seen for a long time.

Using the arrow keys, players explore the virtual city, all the while trying to avoid the runners. If a runner gets too close, players are ‘seen’ and knocked out of the game. This format takes a simple playground game and introduces a twist – of players stretched across physical and virtual space.

Players can use text chat, and runners an open voice channel, to interact with one another in the game. Players’ messages appear on runners’ devices; runners’ walkie-talkie chatter is streamed unfiltered into the online game. Often, this dialogue is based on insults, teasing, goading and humour. The forum is public, shared with everyone in the game, but also allows for players and runners to address each other directly, personally.

Through the live walkie-talkie stream the online players can hear when the runners are tired, cold and struggling, giving an insight into how hard their adversaries are having to work to hunt them down on the streets. A player from Seattle wrote: “I had a definite heart stopping moment when my concerns suddenly switched from desperately trying to escape, to desperately hoping that the runner chasing me had not been run over by a reversing truck (that’s what it sounded like had happened).”

Artists’ Note

Blast Theory, 2003

Can You See Me Now? draws upon the near ubiquity of handheld electronic devices in many developed countries. Blast Theory are fascinated by the penetration of the mobile phone into the hands of poorer users, rural users, teenagers and other demographics usually excluded from new technologies.

Some research has suggested that there is a higher usage of mobile phones among the homeless than among the general population. The advent of 3G (third generation mobile telephony) brings constant internet access, location based services and massive bandwidth into this equation. Can You See Me Now? is a part of a sequence of works (Uncle Roy All Around You and I Like Frank have followed) that attempt to establish a cultural space on these devices. While the telecoms industry remains focused on revenue streams in order to repay the huge debts incurred by buying 3G licenses and rolling out the networks, Blast Theory in collaboration with the Mixed Reality Lab are looking to identify the wider repercussions of this communication infrastructure. When games, the internet and mobile phones converge what new possibilities arise?

These social forces have dramatic repercussions for the city. As the previously discrete zones of private and public space (the home, the office etc.) have become blurred, it has become commonplace to hear intimate conversations on the bus, in the park, in the workplace. And these conversations are altered by the audience that accompanies them: we are conscious of being overheard and our private conversations become three way: the speaker, the listener and the inadvertent audience.

Proximity and distance exist at five levels in the game. Firstly, any game of chase is predicated on staying distant from your pursuer. Secondly, the virtual city (which correlates closely to the real city but is not an exact match) has an elastic relationship to the real city. At times the two cities seem identical; the virtual pavement and the real pavement match exactly and behave in the same way. At other times the two cities diverge and appear very remote from one another. For example, traffic is always absent from the virtual city. Thirdly, the internet itself brings geographically distant players into the same virtual space. It also enables those players to run alongside the runners as it streams their walkie talkie chat. Fourthly, the name of someone you haven’t seen for a long time but you still think of brings someone from the player’s past into the present: their name is spoken aloud by a runner on the distant streets of the city and exists for a seconds before fading into the ether. Finally, the photos taken by runners of the empty terrain where each player is seen are uploaded to the site and persist as a record of the events of each game. Each player is forever linked to this anonymous square of the cityscape.

With the advent of virtual spaces and then hybrid spaces in which virtual and real worlds are overlapping, the emotional tenor of these worlds has become an important question. In what ways can we talk about intimacy in the electronic realm? In Britain the internet is regularly characterised in the media as a space in which paedophiles ‘groom’ unsuspecting children and teenagers. Against this backdrop can we establish a more subtle understanding of the nuances of online relationships. When two players who know one another place their avatars together and wait for the camera view to zoom down to head height so that the two players regard one another, what is going on? Is this mute tenderness manifest to anyone else and should it be?

The work was premiered in Sheffield at the b.tv festival. Other venues include the Dutch Electronic Arts Festival in Rotterdam; the Edith Russ Site for Media Art in Oldenburg; the International Festival for Dance, Media and Performance in Köln; Gardner Arts Centre in Brighton; ArtFutura in Barcelona; the InterCommunication Center (ICC), Tokyo; Interactive Screen at the Banff Center, Canada; Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago; We Are Here 2.0 in Dublin; Donau Festival in Austria; In Certain Places in Preston; Machine-RAUM in Denmark; Picnic Festival in Amsterdam; Arte.Mov in Belo Horizonte, Brazil; ARCO in Madrid and at Tate Britain.

Can You See Me Now? was a collaboration between Blast Theory and the Mixed Reality Lab, University of Nottingham. Steve Benford, Martin Flintham and Rob Anastasi from the Lab made particularly significant contributions to this work. It was commissioned for Shooting Live Artists – a strategic initiative by Arts Council England, BBC Online and b.tv/The Culture Company – in 2001 and was first shown at the b.tv festival in Sheffield on 30 November and 1 December that year. Subsequent presentations in Europe have been supported by The British Council and UK presentations in 2004 and 2005 are supported through Arts Council England’s Grants for the Arts programme. As well as winning the Prix Ars Electronica this work was nominated for a BAFTA in Interactive Arts.

Be the first to experience our new work

Sign up to our mailing list and you’ll receive monthly emails about our upcoming projects, news, competitions and more. Here’s how we use your data and how you can opt-out.